Bronze Age Echoes in Northeast Africa

Global and Local Ancestry Deconvolution applied to human whole genome sequences from Northeast Africa

Supervised by Prof. Pagani (University of Padua + University of Tartu)

Why is this project cool?

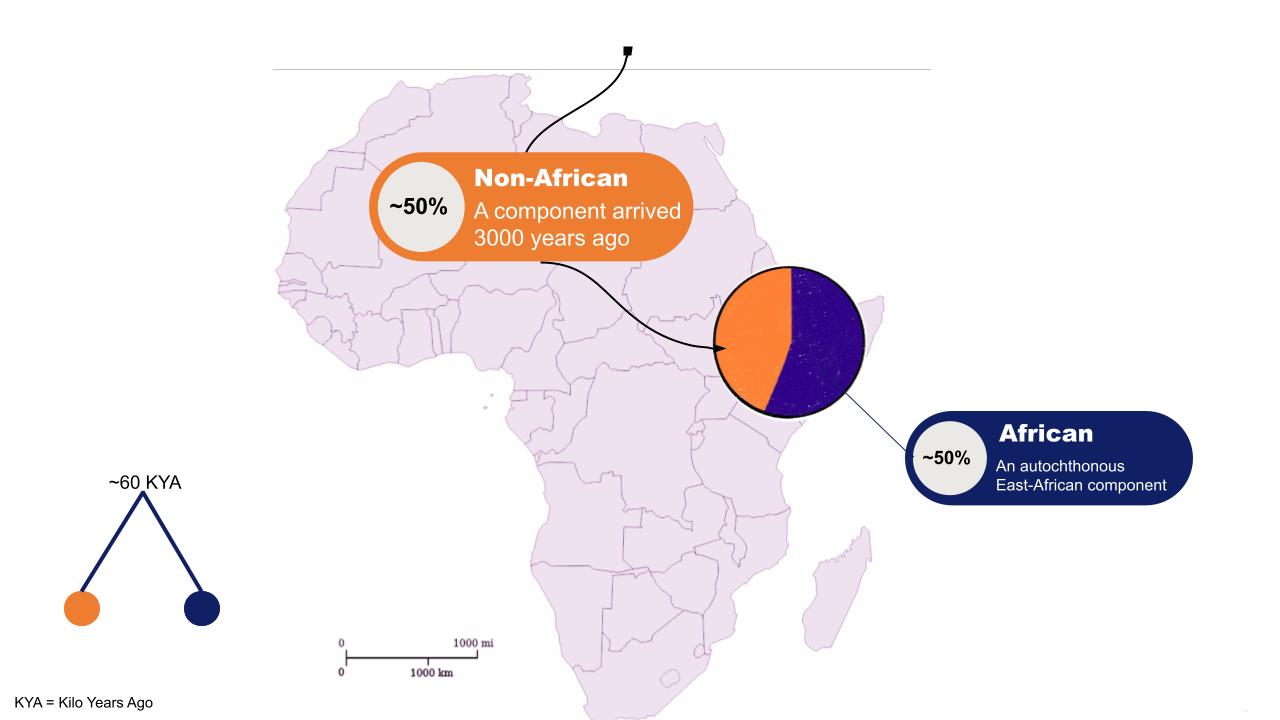

The presence in contemporary Ethiopians of genomic signatures of Eurasian origin has been reported by several authors and estimated to have arrived in the area from 3000 years ago. Several authors have tried to identify a plausible source population for such a signature, using haplotype-based methods on modern data (Pagani 2012) or single-site methods on modern (Pickrell, Hodgson) or ancient data (Lazaridis 2016). These studies did not reach a consensus on the plausible origin and spanned from an Anatolian or Sardinia-like proxy (Pickrell) to a broadly Levantine (Pagani) to a more specifically Levantine Neolithic component (Lazaridis). Given the ancient nature of the Eurasian migration to Ethiopia and the massive population movements and replacements that affected West Asia in the last 3000 years, a natural conclusion would be to rely on the inference made by using ancient data (aDNA) as proxy for the putative population sources. On the other hand, however, the deeply divergent, autochthonous African component which accounts for ~50% of most contemporary Ethiopian genomes was only modelled but not removed from the analyses relying on aDNA. We speculate that the presence of a highly divergent component may affect the overall allele frequency spectrum to an extent that would make it hard to control for it and, at once, to discern between subtly different, yet important, Eurasian sources (such as Anatolian or Levant Neolithic ones).

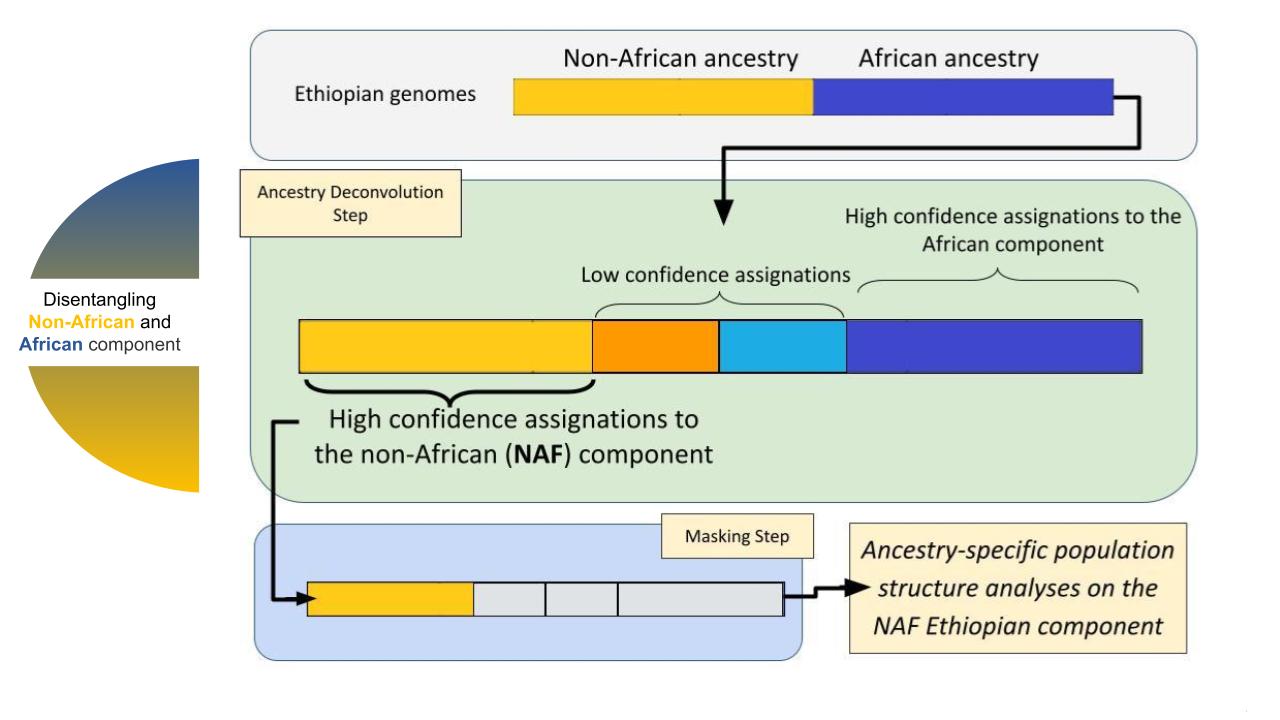

To overcome these potential biases we here propose to re-assess pattern of allele sharing between the Eurasian component of Ethiopians (here called “NAF” for Non-African) and ancient and modern proxies from the Levant and the broader Mediterranean area after having extracted NAF from Ethiopians through ancestry deconvolution. As shown elsewhere (Yelmen et al. 2019) we could therefore i) exploit high quality modern data and ii) concentrate the power of allele sharing tools on genetic fractions with no or reduced African contributions.

Such an approach, while potentially beneficial, may introduce a novel source of bias linked with the performance of the ancestry deconvolution process, which we aim to explore. Particularly, after devonvolving the 120 analysed Ethiopian genomes (Pagani 2015) we assigned each genomic SNP into one of the following four categories based on the method likelihoods: 1) confidently non African (called NAF); 2) grey area, towards non Africa (called “X”); 3) grey area, towards Africa (called “Y”) and 4) confidently African (AF, consistently filtered out from our analyses). While basing our inference on the NAF component alone, we here demonstrate that the component X does account for a minority of the genome and, when analysed together with NAF does not change the quality of our conclusion.

Furthermore, when joining together the NAF and AF confidently assigned components (to created “Joint” components) we recapitulate the signals of the untouched population, showing that the X and Y components are not holding a considerable or peculiar genetic signature and hence ruling out, in this study, the role of ancestry deconvolution as a potential source of artefacts.

A preliminary exploration of the NAF genomes through projected PCA show them to fall among other Eurasian populations, indicating the quality of the deconvolution process, and highlighting an affinity with ancient populations with a high Anatolian Neolithic component (e.g. Anatolia_N and Minoans). Notably, several Jews populations from North Africa cluster with NAF as well. The affinity between Anatolian Neolithic and NAF was further highlighted by f3 outgroup statistics, which contrasted what was observed for the non-deconvoluted genomes. Overall, whole-genome sequences of all the Ethiopian populations appear closer to ancient Near Eastern populations such as: Natufian, Levant Neolithic, Minoans and Anatolian Neolithic. On the other hand, their NAF components appear closer to populations with a high Anatolian component instead of Levant (such as Minoans, Sardinians and Anatolia Neolithic).

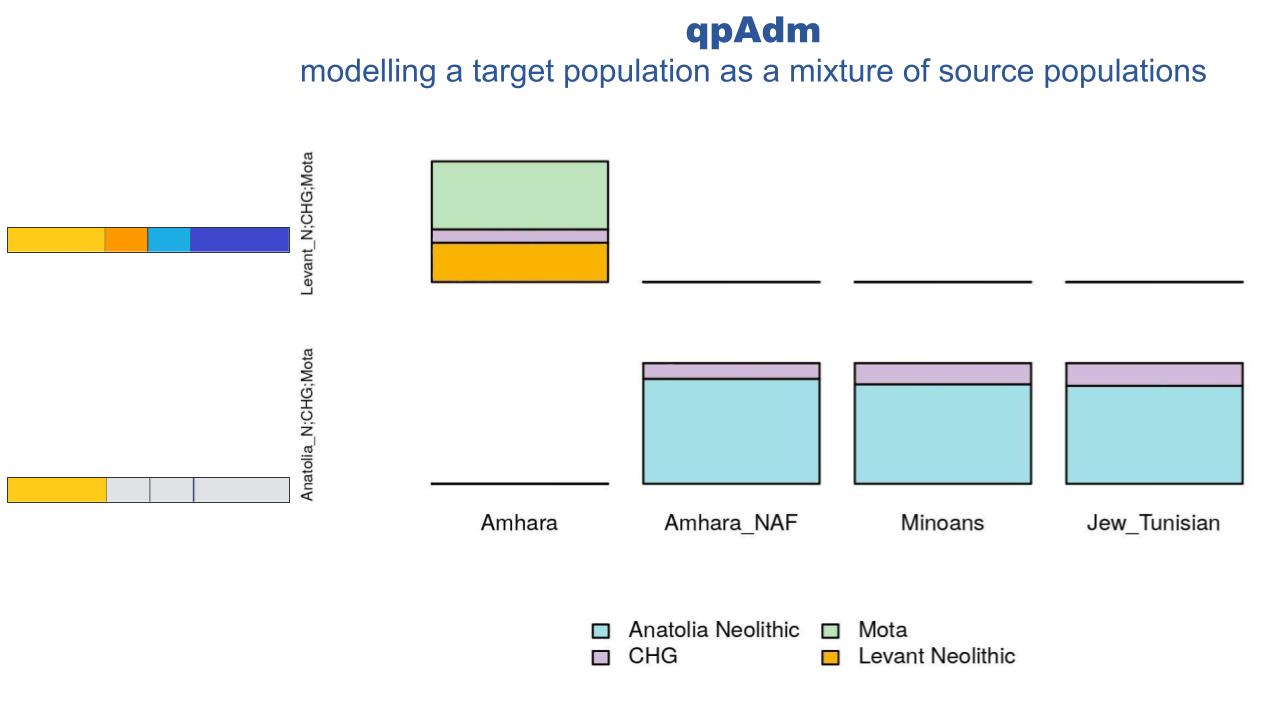

We followed the observed affinity between NAF and Anatolian Neolithic-like populations through a set of f4 tests aimed at refining through more and more stringent comparisons the best proxy population for the Eurasian layer. The whole-genomes, with both African and Non-African components, are significantly closer to a Levantine ancestry rather than Anatolic (Z-Score 2.98), with them being closer to Levant Chalcolithic individuals than Levant Neolithic. On the other hand, the NAF component is shown to be closer to a Neolithic ancestry from Anatolia rather than any Levantine one (Z-score -2.847). We further compare the best proxies for the Non African component using the top scoring populations from Outgroup f3 analyses. Minoans appear to be as close to NAF as Anatolian Neolithic individuals (Z-Scores < 1). Given that our ability to pinpoint the actual source of the NAF component is inherently limited by the availability of ancient and modern populations, we used qpGraph and qpAdm to model NAF as a mixture of the major axes of genetic diversity that best describes the Mediterranean area at the time of the studied event, following Lazaridis et al. 2016. When looking at the untouched genomes, our qpAdm results replicate a Levant_N origin for the Eurasian component of Ethiopians (as in Lazaridis et al 2016). When looking at NAF, such an inference shifts towards a predominant Anatolian_N and CHG composition (~0.85 and ~0.15, respectively), remarkably similar to the modelling of Minoans and Tunisian Jews.

In summary, from a genetic viewpoint, the Eurasian component detected in contemporary Ethiopians and believed to have arrived in the area from around 3 kya can be modelled as 85% Anatolian Neolithic and 15% CHG. While this result should not be interpreted as a connection between Neolithic Anatolia and Ethiopia, it offers a key to identify candidates among the available ancient and modern populations which, following geographic and chronological considerations, may be better proxies for the population or populations that brought the Eurasian component to East Africa. Of the ones analyzed here, Minoans seem to provide the two closest matches to NAF, adding on top of the genetic evidence a criteria of space/time compatibility. In conclusion, our work shows that when the mixing components are deeply differentiated such as in the case of contemporary Ethiopians, ancestry deconvolution increases the sensitivity of allele sharing tests and enables to fully exploit the uncomparably higher quality of modern genomes, which can act as reservoirs of ancient genetic components that would have otherwise been lost or overlooked.

References

2022

- Ancestry deconvolution of Estonian, European and Worldwide genomic layers: a human population genomics excavation2022

2019

- West Asian sources of the Eurasian component in Ethiopians: a reassessmentScientific reports, 2019

2018

-

- Human evolutionary history of Eastern AfricaCurrent Opinion in Genetics & Development, 2018